In Maine, a US federal judge is mulling two questions in a battle over the rights of ship’s crews when their vessel is at the centre of a criminal pollution investigation.

The quandaries can be boiled down to this: if US authorities suspect a ship of an oil-dumping crime, does a court have any say over decisions to effectively confine them on a foreign-flag ship during the investigation and prosecution, even if the seafarers are just innocent witnesses?

The debate emerged as part of a lawsuit filed by three crew members on a German-controlled ship who alleged they were falsely imprisoned when the US rejected their shore passes, struck a deal with their employer to hold their passports and ultimately arrested them when they asked a judge to let them go home.

The case is a key challenge to the controversial practice of holding seafarers as witnesses during investigations for violation of the international Marpol convention regulating pollution from ships.

The seafarers’ lawyers wrote in TradeWinds’ Viewpoint column on Friday that such tactics are a violation of seafarers’ basic rights. But for the government, which has asserted the men were treated fairly and decently, there was an environmental crime to prosecute on MST Mineralien Schiffahrt Spedition und Transport (MST)’s 27,700-dwt slurry carrier Marguerita (built 2016), and the mariners were witnesses to it. (MST ultimately pleaded guilty in 2018 and was fined $3.2m.)

As lawyers await a decision on the US Justice Department’s request for a summary judgment throwing out the case, district judge Jon Levy asked both sides whether he even has the power to review the decision to revoke the shore passes of Jaroslav Hornof, Damir Kordic and Lucas Zak and force them to stay on the vessel.

And, he asked in the March order, do the men even have the right to sue the government under the Federal Tort Claims Act?

According to court papers, the three seafarers had been granted shore passes to leave the Marguerita before the US Coast Guard boarded the vessel to investigate a report that the ship had been dumping oily water into the sea. Hornof had reported the pollution to MST, which voluntarily informed US authorities.

Shore passes

The crewmen’s lawyers, Edward MacColl and Marshall Tinkle of Maine law firm Thompson, MacColl & Bass, said US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) later revoked the shore passes, forcing the men to stay on the ship, even though Zak’s contract had ended and he had tickets to return to Slovakia.

“The summary judgment record includes relevant testimony demonstrating that CBP officials acted not to protect America’s borders, but only to accommodate the Coast Guard’s pre-planned criminal investigation and request,” MacColl and Tinkle wrote.

But the Justice Department’s lawyers responded to the judge by arguing that US law gives authorities wide discretion to issue and revoke landing permits, and the Immigration and Nationality Act restricts the court’s authority to review such decisions.

“Revocation of a shore pass is no different than processing an application for immigration benefits, denying a green card, denying an individual’s naturalisation application, or withdrawing an individual’s citizenship,” wrote US government lawyers led by principal deputy attorney general Brian Boynton.

Right to sue?

Even if the immigration law does not prevent the court from reviewing such decisions, the Justice Department lawyers contended, the claims do not fall under the Federal Tort Claims Act.

This allows litigants to file claims against the US government in circumstances where a private person would be liable for the same actions.

“Where the revocation of plaintiffs’ shore passes is concerned, Maine law cannot possibly impose a duty of care on a private party, because no private person is empowered to regulate ingress at our Nation’s borders,” Boynton and his team wrote.

MacColl and Tinkle, who filed the lawsuit on behalf of the seafarers in 2019, disagreed.

Wide discretion

They argued that even if CBP officials have wide discretion to issue shore passes to seafarers, they do not have such unfettered power when it comes to revocation.

“The revocation statute makes clear the discretion to revoke is conditional and limited,” they wrote.

They argued that revocation can only take place after proceedings determine that the seafarer is not a “bona fide” crewman or does not intend to depart the vessel.

“Determination that a purported crew member is an impostor is a factual determination that, like any administrative decision, must have a demonstrable factual basis,” they wrote.

The lawyers said that applies only to the D-1 passes that Hornof and Kordic received and not Zak’s D-2 pass, allowing him to return home.

“The government lacks authority to revoke D-2 shore passes,” MacColl and Tinkle wrote.

And they argued that the revocations were not immigration enforcement actions but instead “were part of an integrated effort to detain the plaintiffs without judicial process unrelated to immigration matters”.

Kassian case

The seafarers’ case is not the first in which the US government has asserted wide discretion in pollution prosecution against ships. In 2013, for example, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed with arguments that the US Coast Guard had “limitless” discretion in its detention of Kassian Maritime’s 73,500-dwt Antonis G Pappadakis (built 1995). Kassian was ultimately acquitted in that case.

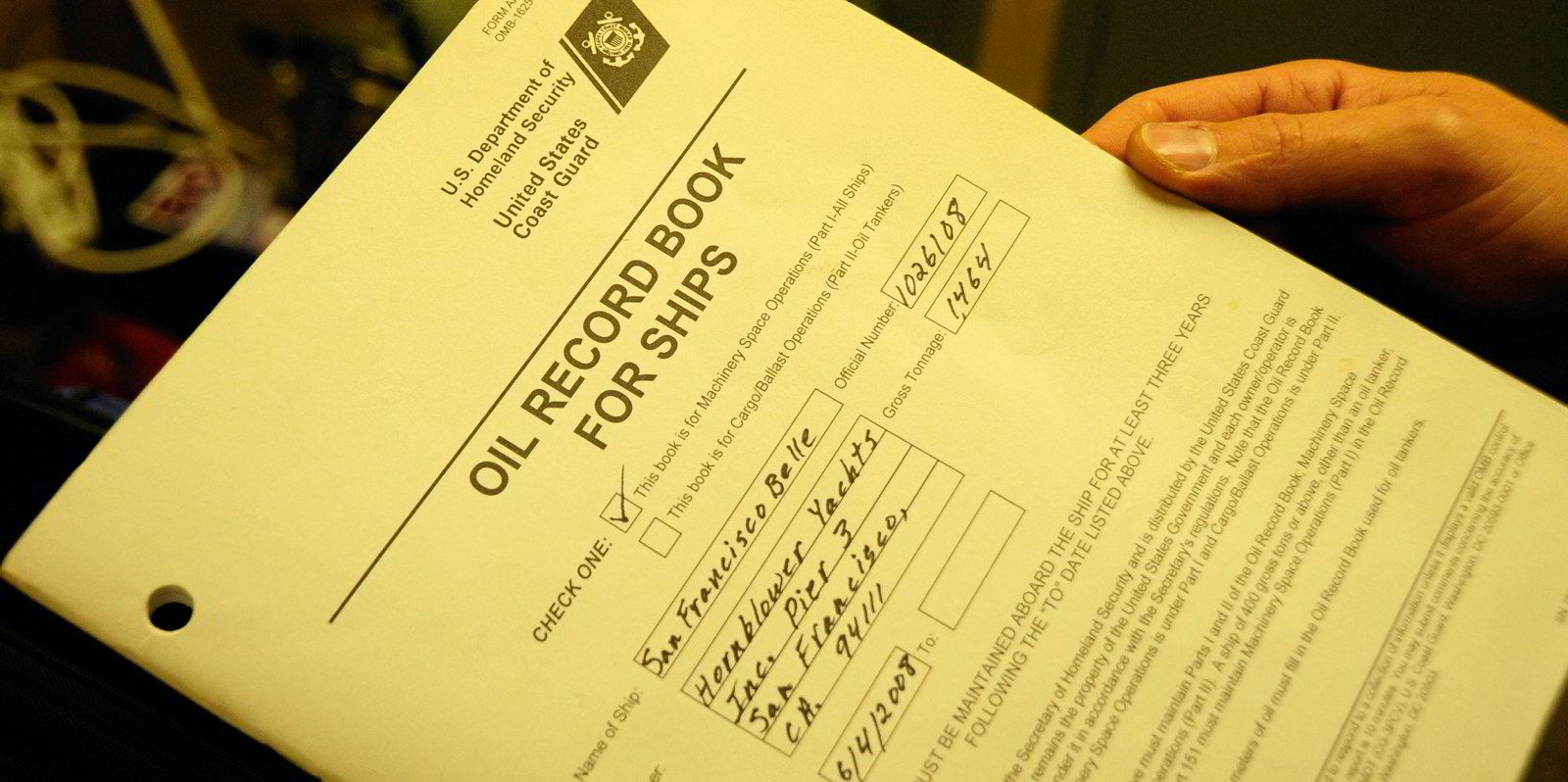

But lawyer George Chalos, the Chalos & Co principal who represented Kassian and MST, said these are not even pollution cases, since the US charges defendants for entries in a ship’s oil record book rather than for the act of dumping oil overboard, which is in the jurisdiction of the flag state.

“It’s not a pollution incident in the US. It’s a record-keeping incident in the US, and the ends don’t justify the means,” he told Green Seas.

The lawyer said such oil record book cases rely on what he described as the perverted notion that the US is the police officer to the world, comparing such detentions to Iran’s seizure of the Chevron-chartered, 159,000-dwt suezmax tanker Advantage Sweet (built 2012) and its seafarers.

“Why is the sauce good for the goose but not for the gander?” Chalos asked.

______________

Viewpoint: How shipowners can limit their exposure to the US’ shameful piracy

The US’ presumptuous worldwide maritime pollution enforcement regime violates foreign seafarers’ basic human rights and the treaty itself, lawyers Edward MacColl and Marshall Tinkle wrote in TradeWinds.

The practice needs exposure and reform, but in the meantime, there are steps shipowners and managers can take to limit their crew’s personal exposure and their own economic costs.

Historically, in the negotiations that led to the Marpol treaty, the US unsuccessfully pressed for enforcement to be put in the hands of port states. Instead, the treaty gave enforcement to flag states, but let port states arbitrate before the International Maritime Organization against flag states in cases of deficient enforcement.

US negotiators told the US Senate that such arbitration would be an “important lever”.

It’s a lever the US has never employed.

Click here to read the column.

______________

Podcast: Time for shipping to get ready for the EU’s new carbon tax

With European Parliament approval in the rearview mirror, shipping will have to shift from wait-and-see mode to getting ready for what is effectively a tax on greenhouse gas emissions, as the Green Seas audio edition explores.

That is because part of what was approved involves folding shipping into the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS), starting in 2024.

Under the law, shipping companies will have to buy carbon credits known as allowances for their emissions on voyages within the EU, but also voyages between the 27-nation bloc and other parts of the world.

Click here to read the article version. Subscribe to the podcast on Google Podcasts, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Pandora, Spotify or SoundCloud.

______________

Russia vows to investigate suspected Black Sea oil spill

Upstream reports that Russian authorities have finally promised to open an investigation into a suspected oil spill near the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk that was spotted by residents on Monday, but had been causing a bad smell for weeks.

A prosecutor’s office at the Krasnodar region, where the port is located, said it is “checking the compliance with the requirements of environmental legislation in the implementation of port [loading] activities”.

After tip-offs from residents, Russia’s environmental protection agency, Rosprirodnadzor, said it had found “an iridescent spot of about 40 thousand square metres on the surface of the sea” that may have been a spill of oil and products.