Voices in shipping had been warning for months about the risk of an oil spill from the fleet of tankers trading in the shadows following sanctions against Russia.

And it appears such a spill may have happened, although fortunately the worst has been averted because the tanker had no cargo.

After the 96,800-dwt aframax Pablo (built 1997) suffered an explosion off Malaysia, media in neighbouring Indonesia reported an oil spill at Kampung Melayu Nongsa in Batam, a city in the country’s Riau Islands.

The spill could have been worse, but the Pablo was in ballast at the time of the incident, meaning it had no crude cargo, although it certainly had fuel oil in its bunker tanks, which is similarly damaging to the environment.

That has led many maritime safety experts to point to the incident as an alarm bell about the shadow or “dark” fleet.

Copenhagen University maritime security expert Jan Stockbruegger had been raising concerns about the dangers of shadow tankers, and he said the Pablo incident highlights those worries.

“This is the risk when you have a very old tanker not properly regulated,” he told TradeWinds.

‘Warning call’

“I hope that this is a warning call for everyone and we take this issue much more seriously and try to address it.”

Rolf Thore Roppestad, chief executive of protection and indemnity insurer Gard, told Bloomberg that the explosion is a “stark reminder” of the risks that experts have been warning about.

“The shadow fleet poses a serious threat both to people’s lives and to the marine environment,” he said.

“What worries me is that there are ships like these passing through high-traffic straits every day. So the likelihood of more accidents like this happening is actually quite high.”

Outlining the risk

Why are shadow fleet vessels so dangerous?

One key reason is that the lucrative trades that serve Russia’s oil cargoes, in addition to those of other sanctioned exporters Iran and Venezuela, are extending the life of older tankers that would have otherwise been retired.

TradeWinds has reported that research by shipbroker Braemar shows that the proportion of tankers aged 20 years or more has increased from 2.2% in 2019 to nearly 8% today.

The shipbroker believes the proportion of ships that are 20-plus years is likely to rise to 15.5% by mid-2025.

In the dark

And the shadow fleet gets its name from the fact that its vessels operate in the dark recesses of the international safety regime, eschewing the mainstream insurance providers, classification societies and shipping flags, and ownership of the ships is often unclear.

TradeWinds journalist Paul Peachey has reported that the Pablo was stripped of its flag three times in 16 months, following claims of involvement in trading sanctioned Iranian crude.

The ship’s flag state at the time of the incident was Gabon. That is not a blacklisted shipping registry only because port-state control officials have not inspected enough of its vessels to factor in the rankings.

The recently released Tokyo MOU on Port State Control annual report shows nations that are involved in the rankings have inspected Gabon-flagged vessels only 24 times in the past three years, below the minimum 30 inspections to get on the flag state rankings.

And who insured the Pablo? At this stage, nobody knows.

Its owner and manager, Pablo Union Shipping, is known by name only.

TradeWinds reported that the company was set up this year and is believed to be a special purpose vehicle.

Pablo Union Shipping is a Marshall Islands company with the Trust Company Complex in the capital, Majuro, as its address, according to the country’s corporate registry. But as is typical for open registries like the Marshall Islands, no information on its shareholders are available.

Classification societies are a key layer of safety for ships, but none is currently listed for the Pablo. Equasis data shows that the Polish Register of Shipping withdrew classification at the request of the tanker’s owner in December, and there is no replacement on record.

Captain Andrew Parker, a master mariner who is managing director of consultancy Ankar Maritime Safety in the UK, had strong words on LinkedIn for ships with the profile of the Pablo.

“These so-called ‘dark fleet’ vessels are a stain on our industry and international action is needed to stop them from sailing the oceans,” he wrote.

_______________

Wilson Sons cuts greenhouse gas emissions at port terminals and in tug fleet

Brazil’s Wilson Sons reported a cut in its greenhouse gas intensity and a boost in the percentage of women in its workforce.

The Sao Paulo-listed tug and terminal operator reported just over 63,900 tonnes of combined Scope 1 and Scope 2 CO2-equivalent emissions last year, a 4.8% dip from the greenhouse gas footprint in 2021, according to a sustainability report.

That included nearly 62,400 tonnes of direct Scope 1 emissions in 2022 and 1,516 tonnes of Scope 2 emissions, which involve energy purchased to power its operations.

_______________

Podcast: How companies are tackling an ocean-size gap in data about the sea

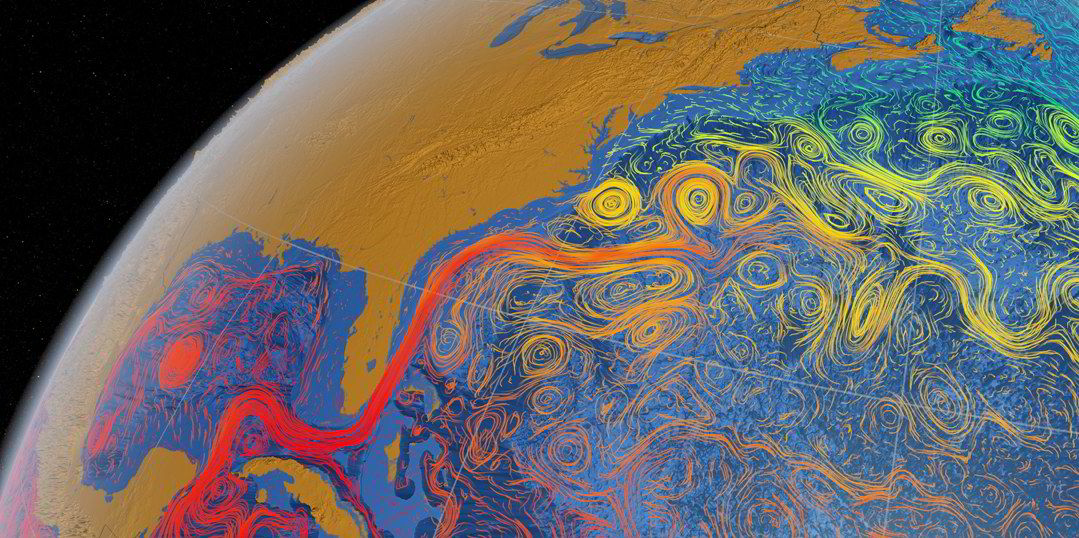

Tim Janssen, an oceanographer who spent much of his life focused on how the seas interact with the atmosphere before co-founding technology firm Sofar Ocean, says humanity is good at collecting large amounts of data.

But he estimates that data on the ocean is about 11 orders of magnitude behind. And that gap is compounding every year.

Yet there are companies that are contributing to closing that data gap by using their assets at sea to collect information about the ocean and the climate above it, as the Green Seas audio edition explains.

Click here to read the article version, or find the episode on Google Podcasts, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Pandora, Spotify or SoundCloud.

_______________

A fisherman caught what he suspected was an escaped farmed cod. The lab results have now come back

The crew of a fishing boat working off the village of Laukvik, Norway, noticed something abnormal about one of the cod pulled up in their nets over Easter.

The head of the three-kilogram fish was small and deformed, there was something strange about the neck and the liver was snow-white, skipper Benn Ole Stensvold told fishing industry news service Fiskeribladet.

The fish was picked up on the quay by the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries, which took samples and sent them to the country’s Institute of Marine Research for analysis.

The Directorate of Fisheries has now released its findings: the cod was raised on a farm.

In recent months, Norway’s burgeoning cod farming industry has come under fire following multiple reports of escaped fish and speculation over their potential impact on wild populations.