A few months ago, climate futurist Alex Steffen started describing the moment we’re living in now as the “trans-apocalypse”.

The term is dramatic (though not meant to be end-of-the-world dramatic) as it describes climate change as a planetary crisis that’s happening now and whose effects we have to prepare for urgently.

And while it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t work to stop climate change from becoming a runaway train, the concept of “trans-apocalypse” suggests it’s a train we’re already on and we have to adjust to that fact.

It’s time to build resilience to the effects of climate change.

In the maritime business, a key area of vulnerability is ports, because of their exposure to rising seas and extreme weather.

And yet researchers focused on ports and their role in global trade believe the focus for the port sector remains climate change mitigation — that is, efforts like decarbonisation aimed at slowing global warming.

But cutting greenhouse gas emissions bears fruit in the long run, while ports are expected to feel the impact of climate change in the near term.

Regina Asariotis, chief of trade logistics policy and legislation at the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), pointed out that some 80% to 90% of world trade is carried by sea, making ports critical to supply chains. And they are particularly essential to small island states, where they are not only key for bringing in food, energy and tourists but also disaster relief.

Impacts of climate change

And yet, ports are exposed to coastal flooding from rising oceans, including extreme sea levels in times of storms. While ports have often been constructed for 100-year extreme sea levels, even if global warming is capped at 1.5C, those conditions could happen every five years in many tropical and subtropical parts of the world.

“What is at stake is global trade and sustainable development,” Asariotis said. “And that, of course, affects the world’s poorest countries most, including the small island developing states that depend on these transport assets as lifelines.”

What needs to change? Each port’s situation is different, so Asariotis said they need to carry out a risk assessment.

“Risk assessment is the most important to start with, because you have to assess how a particular hazard is going to affect you. That, for example, depends on elevation. That depends on where you have certain assets. It depends on how components are linked in a port.”

For Fernando Leon Mateos, a researcher at Economics and Business Administration for Society (ECOBAS) at Spain’s University of Vigo, what is key is systematising the evaluation of ports’ resilience and continuous improvement.

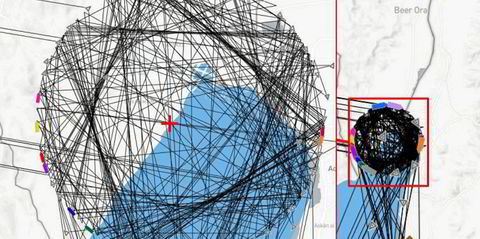

To that end, ECOBAS developed a port resilience index aimed at allowing to evaluate their vulnerabilities based on their specific circumstances.

“The process of increasing resilience must be systematised, with continuous actions in the short term but always taking into account a long-term time horizon,” Leon told Green Seas. “When we talk about climate change, we do not expect changes to take place in one or two years.”

Some ports are taking action.

ECOBAS researchers applied their port resilience index to Spain’s A Coruna, finding that the port had a resilience level of 51.8%, according to a study published in May. A score of 80% is seen as a reasonable target (100% is the top score but is not seen as practical.)

Leon said the port has subsequently raised that score by 15 percentage points toward the target.

In the US, ports are already facing the impact of drought, which hits their power supply, and extreme weather events like hurricanes.

Infrastructure bill

A recently passed infrastructure spending law adds $450m per year for five years to a $230m annual budget for a port development programme, and it adds climate resilience to the type of projects covered by the scheme.

Much of the $17bn in overall spending goes to the Army Corps of Engineers, which maintains waterways, with some of that money also tackling the impacts of rising sea levels.

“We’re very grateful for this funding, but not contented,” said Ian Gensler, government relations associate at the American Association of Port Authorities. “Whether its resilience to climate change or funding for cargo handling equipment, more investment is going to be needed than what’s in this bill.”

For UNCTAD’s Asariotis, the approach that is needed is “all hands on deck”.

“Accelerated action is is is needed to prepare because the projections are getting worse and worse,” she said.

After all, ports are meant to be built to last.

More news on sustainability and the business of the ocean

- Say no to carbon offsetting. That’s the conclusion of TradeWinds reporter Adam Corbett, who describes in our Comment column that offsets could serve as a get out of jail free card for shipping, allowing them to continue burning fossil fuels on their vessels. “The net result could be that offsetting will actually encourage shipping companies to slow down on their decarbonisation efforts. Click here to read the story.

- An explosion involving a floating production, storage and offloading vessel off Nigeria has also resulted in an oil spill. Satellite images show a sheen stretching at least 20 km from the incident. Upstream reports that some 50,000 barrels of oil have been spilt. Click here to read the story.

- Japanese shipowner Mitsui OSK Lines has signed a memorandum of understanding with Malaysian oil company Petronas to study liquefied CO2 transportation for carbon capture, utilisation and storage. MOL’s role in the project will be to study tankers to carry the captured carbon. Click here to read the story.