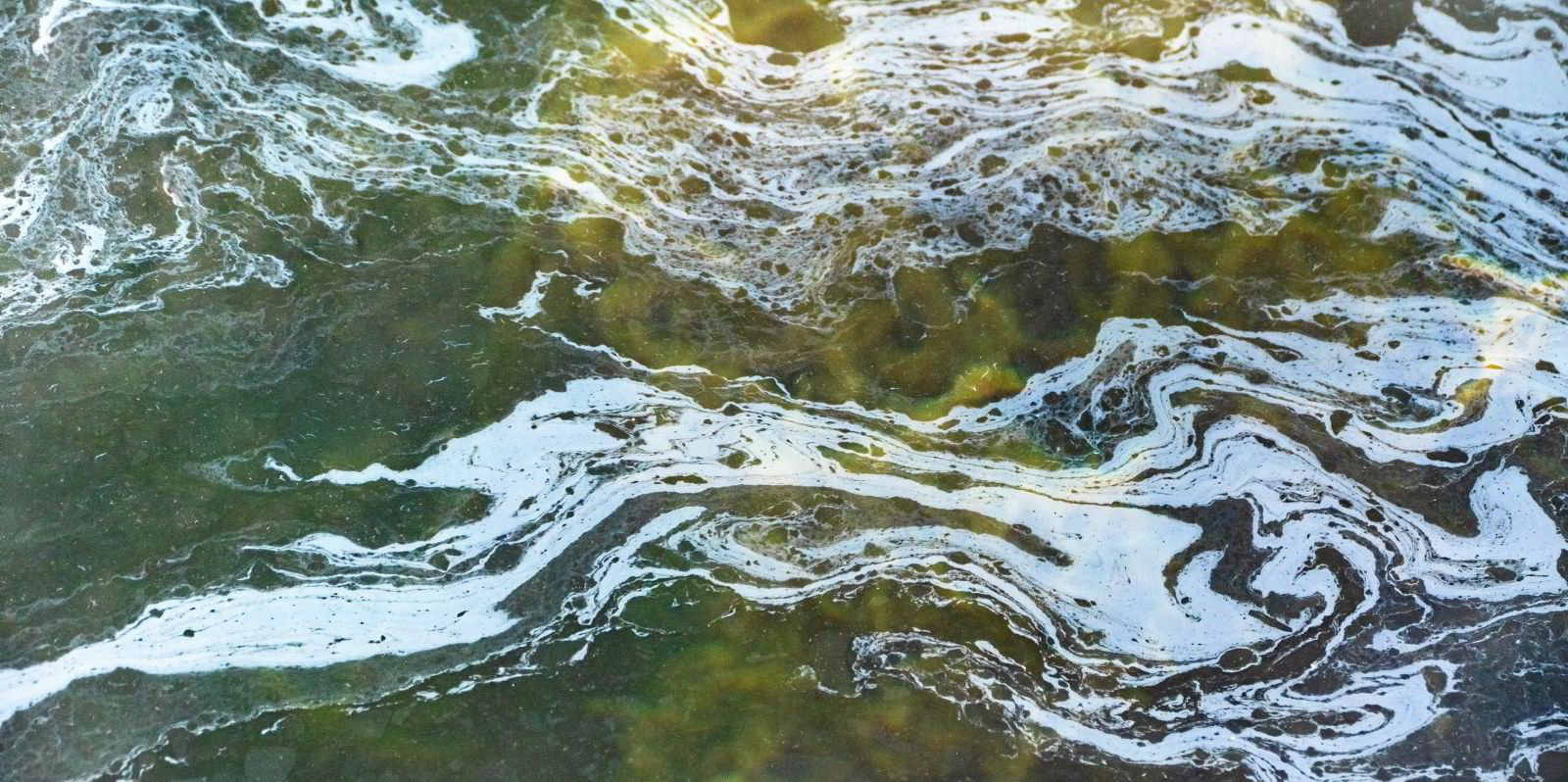

A suspected oil slick the size of 24,000 football pitches has been making headlines in Brazil.

But SkyTruth chief executive John Amos told TradeWinds’ Green Seas podcast that the pollution, which is believed to have emanated from a tanker, is what his organisation sees every day.

He said the slick, which has an area of 170 square km, is typical of discharges from a large moving vessel.

“This was not at all uncommon,” he said. “We see slicks like this on a daily basis around the world.”

SkyTruth’s Cerulean platform identifies the likely source of the oil slick as the 19,800-dwt chemical tanker PVT Sunrise (built 2011), which is owned by PetroVietnam. After we first published this article, shipping unit PetroVietnam rejected the vessel’s link to the oil slick.

The company said the tanker had no cargo at the time, and there was no evidence that oil leaked from the ship.

Brazilian environmental group Arayara Institute said it reported the oil slick to federal authorities in late January, using data from SkyTruth, a non-profit organisation that uses satellite data to spot pollution. The incident took place in September 2023, according to Cerulean.

At the time, Arayara identified the suspected vessel only as a Panamanian-flag ship.

Joao Paulo Capobianco, executive secretary of the federal Environment & Climate Change Ministry, later told reporters that the Brazilian Environment & Resources Institute is investigating.

He said in a report by radio network CBN Amazonia that the navy was working to identify the vessel involved.

Amos told Green Seas that, whatever ship was the source had passed off the edge of the satellite image by the time the suspected oil slick was visible.

Aligned closely

By analysing automatic information system ship tracking data, SkyTruth identified the PVT Sunrise as the likely source of the pollution.

Amos said the vessel’s track aligned very closely with the slick.

“From our perspective, it was a very high-confidence match,” he told the podcast. “Now, a caveat: it’s not [a] 100% sure thing, partly because not all vessels are broadcasting AIS that should be. There are lots of dark vessels operating out of the ocean.”

The number of dark vessels not broadcasting a location is proliferating at the moment, as vessels operating in trades subject to sanctions turn off their AIS transponders to obscure their activities.

Amos said SkyTruth cannot be 100% certain what the slick is made of, such as whether it is hydrocarbons or vegetable oil residue.

The Arayara Institute has used the Cerulean data to urge Brazilian officials to find answers.

“One of the intents with Cerulean is to make all of this information available for free, [to make it] as easy as possible for people who are in a position to start asking some hard questions and, hopefully, get some good answers to those hard questions, to give them what they need to start raising a hue and cry about … this too long ignored pollution problem out on the ocean,” Amos said.

Extrapolating from what SkyTruth’s recently launched Cerulean monitoring system has found so far, the organisation estimates that 18.7m barrels of oil are discharged every year from shipping.

Amos founded SkyTruth 20 years ago.

After spending a decade as a geologist who used satellite imagery and remote sensing technology to create exploration studies for energy and mining companies, he had become convinced that climate change and other environmental issues were problems that the same technology could help tackle.

The organisation has grown to a team of 16, including data scientists, computer programmers and remote sensing specialists to do just that.

Its newest tool on that mission is Cerulean, which was launched in December. It combines satellite imaging technology with machine learning and ship tracking data.

“Cerulean addresses a problem that has personally vexed me since my very earliest days of looking at satellite imagery more than 30 years ago,” Amos said.

He would be looking at satellite images and see long, dark oil slicks that clearly came from ships.

“It seemed like this was wrong. This is a kind of egregious chronic form of pollution that nobody was aware of.

“Because if it’s happening more than 20 miles offshore, it’s kind of below the horizon and out of sight until that nasty oil slick a couple of days later.”

Amos said governments need to take more action and make information about oil pollution from ships transparent.

Cerulean makes data available free only for part of the world, and Amos said there are highly capable, commercially available data platforms already out there. That means officials should be able to have a better measurement of how bad the problem is in their waters and who the perpetrators are.

“There’s no excuse for coastal governments to not be aware of this problem,” he said.

Amos also said the reason ships might be dumping oil at sea needs to be addressed.

For example, there are not enough places to dispose of oily waste in ports, and ships face commercial penalties for diverting off their routes to get to them.

“Figuring out what needs to happen to change that equation and at least remove the incentive for these discharges to continue happening — I think that’s the next step,” he said.