As a resident of South Florida, I could not help but get wrapped up in last month’s playoff excitement.

This region’s Miami Heat basketball team and Florida Panthers ice hockey squad simultaneously reached their respective championship series, despite their middle-of-the-pack records in the regular season. (They both finished in a respectable second place.)

But to turn this into a metaphor about decarbonising shipping, let’s focus on the Heat and its linchpin player, Jimmy Butler. Everyone was watching for him to lead the team and carry the playoffs, but he could not deliver that in every game, so the team’s post-season success often depended on the performance of lesser-known players on a deep bench.

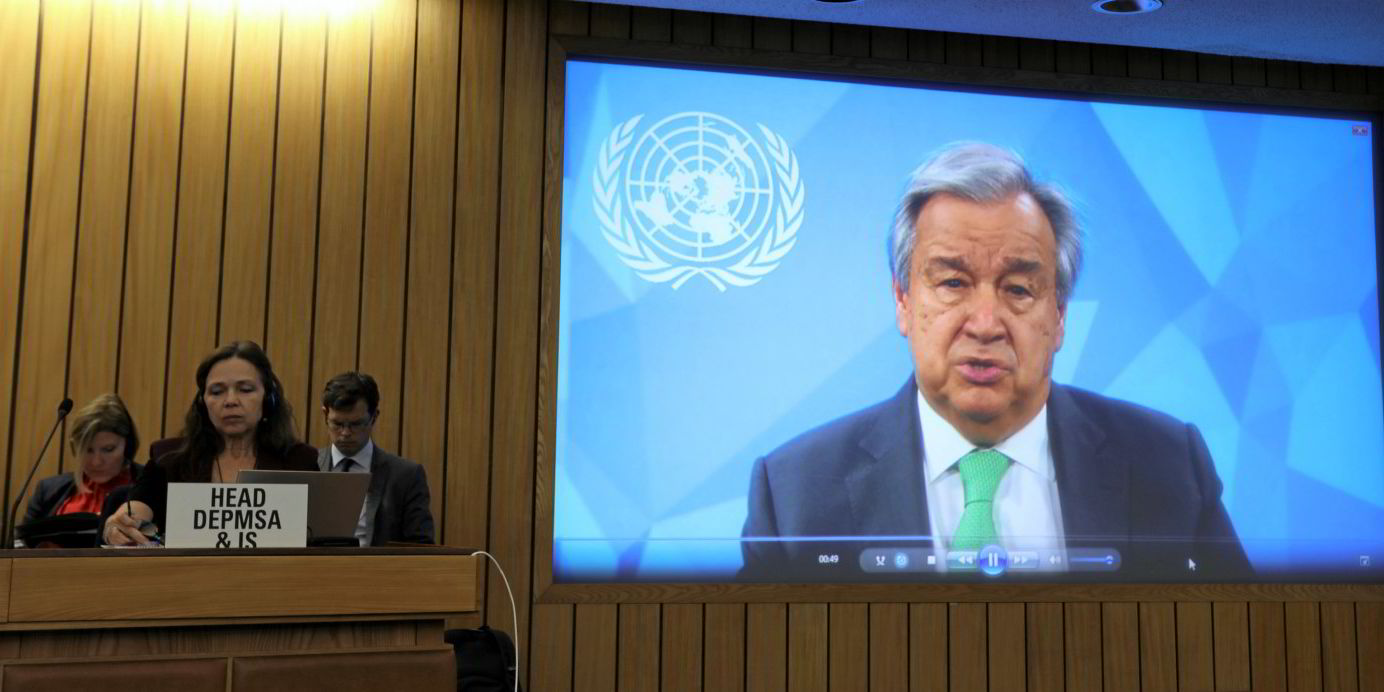

Last week’s resolution by the International Maritime Organization made progress towards reducing shipping’s greenhouse gas footprint, but it was no slam dunk, if the goal is for the industry to do its part in keeping global temperatures from rising more than 1.5C.

The decision taken by the United Nations’ shipping regulator highlights that like Playoff Jimmy — as Butler is known — the IMO will be just one member of the team in order to achieve that victory.

While there is still ample opportunity to push the London-based organisation to do more, staving off the worst effects of climate change will ultimately require actions by other members of the team, including national governments, European Union regulators and private sector initiatives.

“This is a transition which isn’t driven only by the IMO. It’s driven by a combination of IMO regulation, regional, national and industry actions,” UCL Energy Institute associate professor Tristan Smith told me on the Green Seas podcast.

As TradeWinds has reported, the IMO has adopted a target of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by around 2050, and it approved “indicative checkpoints” calling for a 20% to 30% cut in 2030 and a 70% to 80% reduction in 2040.

Disappointed greens

Environmental groups have understandably expressed their chagrin at the targets’ underwhelming ambition and language that is full of wiggle room.

But it is important to remember that the IMO was targeting cuts of just 50% before last week’s resolution of its Marine Environment Protection Committee. The new ambitions represent a significant improvement in an international body that relies on consensus among its member states.

Yet, these targets are not enough.

The IMO member states and experts that were calling for a 37% cut in shipping’s greenhouse emissions in 2030 and 96% in 2040 did not pull these numbers out of the air. They are not arbitrary.

Before the MEPC vote, a senior official in the Biden administration said these goals, which the US delegation favoured in the negotiations, are aligned with the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), a non-profit private sector effort to certify that companies’ decarbonisation goals conform to a trajectory that would help halt global temperature rises at 1.5C.

While the IMO’s new trajectory disappointed some, it will be up for review in five years, and the UN body can still make significant headway in important discussions to come.

The IMO will also review the Carbon Intensity Indicator, which could use enforcement teeth and the inclusion of other greenhouse gases. The regulator also has agreed to introduce midterm measures, including putting a price on carbon and adopting rules to limit greenhouse gas intensity of fuels, by 2027.

But even though many in shipping would like to see the IMO in a monolithic position as shipping’s sole regulator, this week much focus will need to turn to national and regional governments. The European Union has already adopted a package of legislation that includes adding shipping to its Emissions Trading System and promulgating green fuels legislation. There is little doubt that more work is in store for Brussels.

In the US, provisions of last year’s Inflation Reduction Act are expected to give a boost to green fuels production, and lawmakers have introduced legislation to regulate emissions of ships that call in the country’s ports, although those bills will likely take a change in the composition of Congress before they have any chance of passing.

Voluntary action

In the private sector, the SBTi is just one scheme that is helping to drive voluntary action. TradeWinds reported last week that major shipping companies are working to develop “book and claim” systems to allow shippers to pay for voyages using green fuels even if they are physically used elsewhere.

That is under the Global Maritime Forum umbrella, as are the Poseidon Principles that aim to benchmark ship finance and marine insurance against decarbonisation targets, and the Sea Cargo Charter that aims to do the same in chartering.

Those initiatives have just become more important, as long as they continue to lead rather than follow the IMO.

More on the IMO’s carbon decision

- IMO head says 2040 emission target will be ‘extremely challenging’ for shipping

- Podcast: How IMO’s decision on shipping’s carbon still leaves Paris Agreement goals within reach

- Scandinavian shipping groups cheer IMO’s net zero ‘at or around’ 2050 agreement

- Shipowners will do ‘everything possible’ to achieve new IMO goals

- IMO lines up carbon pricing mechanism commitment by 2025