The International Maritime Organization has agreed to new greenhouse gas targets that, while more ambitious than its current objectives, fall short of calls to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement to keep global temperature rises below 1.5C.

Environmental groups said on Thursday that the United Nations shipping regulator agreed to a qualifier-laden target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions at or around 2050, to the extent that national circumstances allow.

And the IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) concluded on “indicative checkpoints” that would seek to cut emissions by at least 20% in 2030 while striving for a 30% cut.

Asked to confirm the agreed targets, IMO spokeswoman Natasha Brown said the final text of the decision will be formally available on Friday.

Environmental groups and researchers had already said that such targets, which are similar to those in a draft that emerged from an IMO working group last week, would fall short of goals that align with capping global heating at 1.5C.

Several nations in the Pacific Islands, Europe and North America had been seeking a 37% cut by 2030 and a 96% reduction by 2040, mirroring the Paris Agreement-aligned trajectory of the Science Based Targets initiative.

But China, Brazil and Argentina were among the countries that pushed back against such ambitious targets, even as they also resisted a carbon levy as a means to get to them.

Clean Shipping Coalition president John Maggs, whose organisation is an alliance of environmental groups calling for a 50% cut at the end of this decade, described the MEPC’s final deal as a “wish and a prayer agreement” even though delegates knew what science called for.

“The level of ambition agreed is far short of what is needed to be sure of keeping global heating below 1.5C, and the language seemingly contrived to be vague and non-committal,” he said.

‘Admirable fight’

“The most vulnerable put up an admirable fight for high ambition and significantly improved the agreement, but we are still a long way from the IMO treating the climate crisis with the urgency that it deserves and that the public demands.”

Madeline Rose, deputy executive director and senior campaign director at Pacific Environment, said the shipping industry will exhaust its carbon budget for a 1.5C trajectory by 2032 under the goals set in the MEPC agreement.

“Nations failed this week to put the global shipping industry on a credible 1.5C decarbonisation pathway,” she said.

Transport & Environment shipping programme director Faig Abbasov said it is hard to think of an international organisation more useless than the IMO, with the exception of international football body FIFA.

“This week’s climate talks were reminiscent of rearranging the deckchairs on a sinking ship,” he said. “The IMO had the opportunity to set an unambiguous and clear course towards the 1.5C temperature goal, but all it came up with is a wishy-washy compromise.”

Several of the environmental organisations that complained about this week’s IMO decisions called for measures outside of the UN body, with action from the private sector, the European Union, the UK and other countries.

Aoife O’Leary, director of the Skies and Seas Hydrogen-fuels Accelerator Coalition (SASHA Coalition), pointed to the IMO’s agreement to strive for zero-emissions sources to make up 10% of shipping’s energy use by 2030, but with measures to reach that targeted for 2027 at the earliest.

“That’s why it’s even more urgent now that the EU, the UK and other countries put in place a decisive national or regional policy to ensure that truly sustainable alternative fuels are available for the shipping industry,” she said.

“The SASHA Coalition will continue to work with its members to ensure that even with this disappointing IMO outcome, the sector will still have access to the fuels it needs to decarbonise.”

Rasmus Bjerring Larsen, shipping policy officer at Green Transition Denmark, said it is clear that a broad majority of countries are ready for urgent climate action, as are progressive shipowners.

“In this light, it is a real disappointment that the IMO could not agree to phase out fossil fuels by 2050,” he said.

“It is now up to industry, progressive member states and regions such as the EU to push beyond what the IMO could agree to, and bring shipping in line with the 1.5-degrees target.”

Read more

- From well to wake: How fuels’ lifecycle emissions are key to IMO greenhouse gas debate

- Levy row takes its toll on IMO decarbonisation talks

- ‘Shipping needs the political will’ to secure carbon consensus, says Ardmore’s Anthony Gurnee

- Major shipping companies commit to ‘book and claim’ system for voluntary green freight market

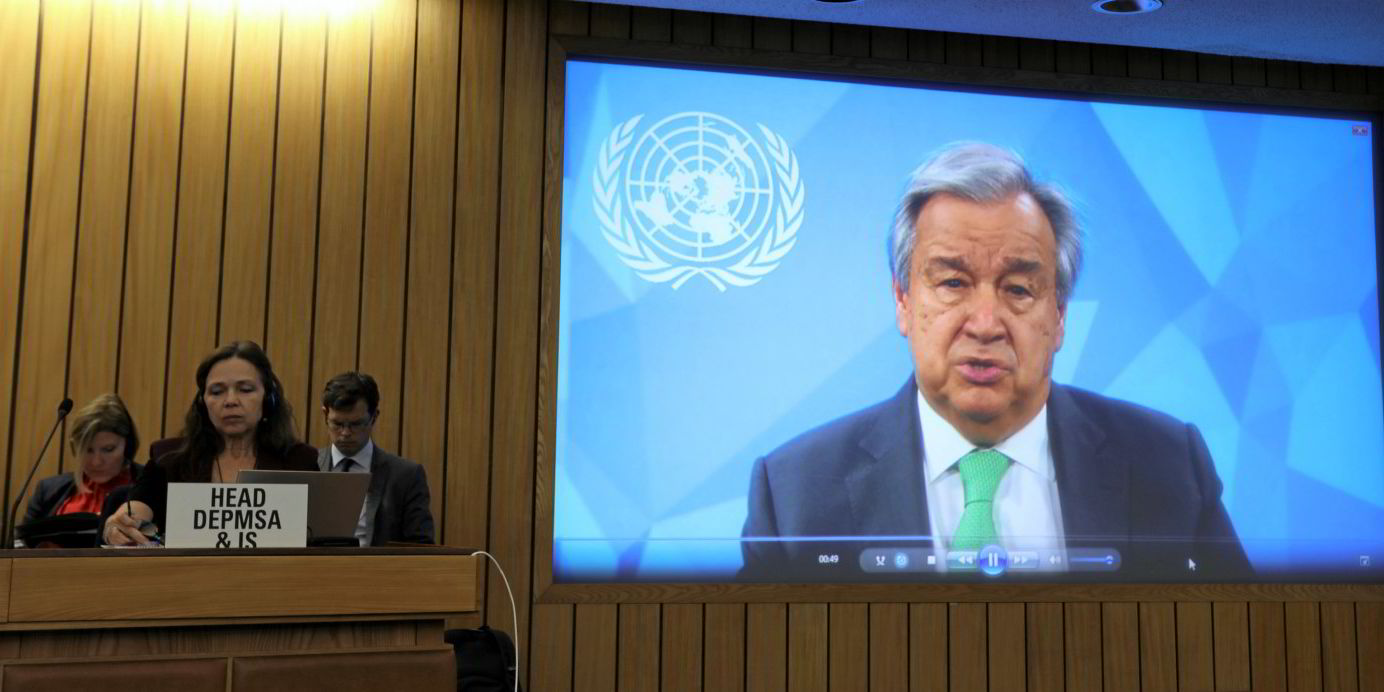

- UN head Guterres says IMO must ‘move much faster’ as climate talks kick off