Wind is free, it’s abundant and it powered shipping for thousands of years before the industry first got hooked on fossil fuels.

But when agricultural giant Cargill and BAR Technologies started working together on wind-assisted propulsion, they sought out to reinvent the sail.

UK-based BAR’s chief executive John Cooper said Cargill asked his technology company, which was founded in 2016 by members of the British team in the America’s Cup sailing competition, to use its simulation methods to study a variety of options to bring wind propulsion to its ships.

“We gave them an honest appraisal. And they said, ‘Could you invent one?’” Cooper said. “We said yes, and WindWings was born.”

A Cargill-chartered kamsarmax bulker has now set sail after the installation of two WindWings sails that the two companies expect to yield significant fuel savings at a time when shipping companies are exploring a plethora of technologies to harness the wind to tackle greenhouse gas emissions.

But the major commodities’ company’s move into operating a wind-propelled ship is one step before another test: how to scale up the technology to make an impact across more of its primarily chartered fleet.

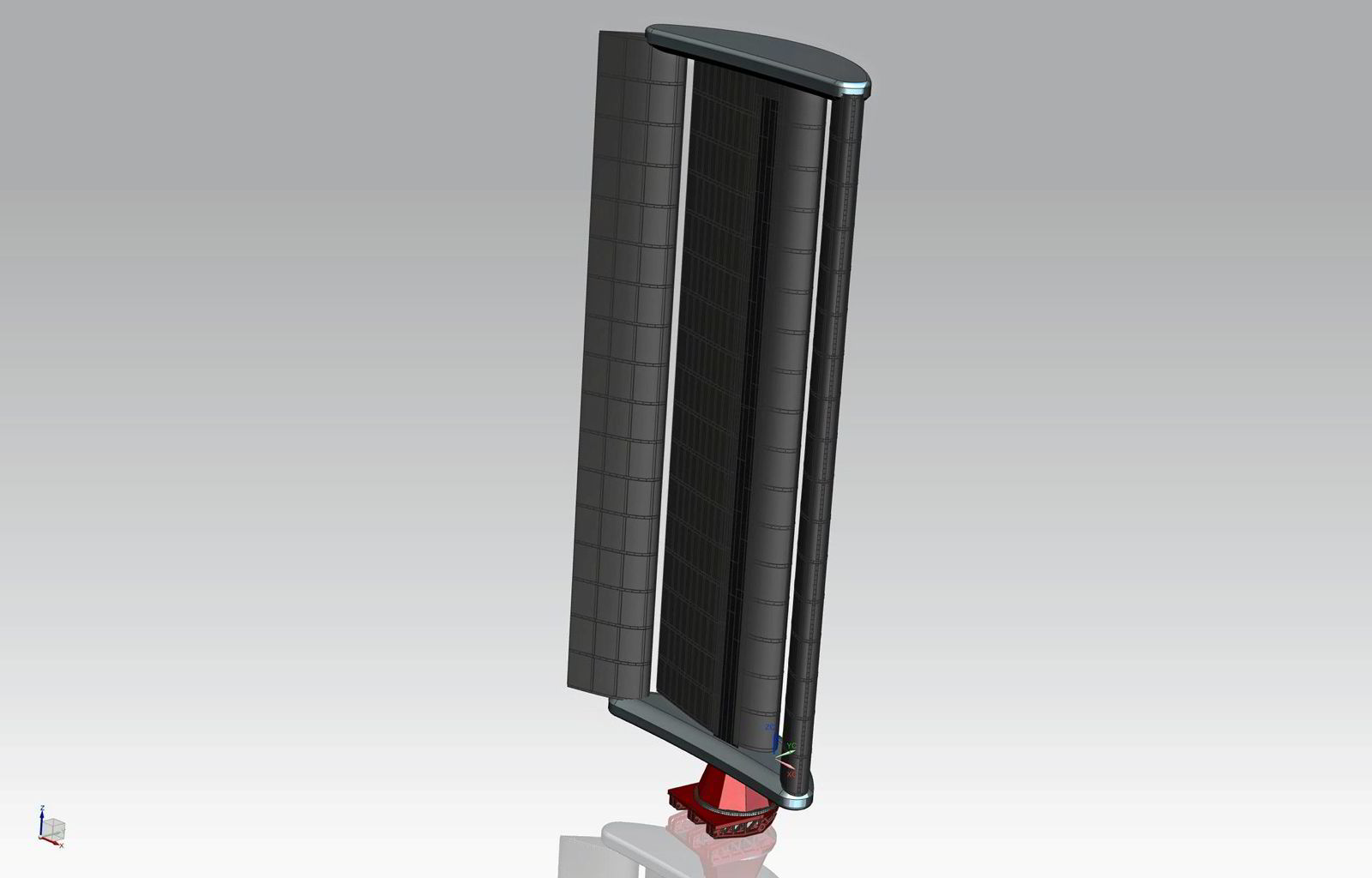

The 37.5-metre rigid sails, built by Yara Marine, were installed on Mitsubishi Corp’s 81,000-dwt Pyxis Ocean (built 2017) at a Cosco Shipyard Group facility in China. The project has the help of European Union funding.

For US-headquartered Cargill, the wind-propulsion retrofit is part of a process to cut emissions in its chartered fleet that has also included a significant move into biofuels and orders for the first bulkers powered by methanol.

Win-win today and tomorrow

Jan Dieleman, president of the Geneva-based Cargill Ocean Transportation unit, said that the deployment of the first WindWings-propelled vessel shows that by getting the right people around the table and being willing to innovate, solutions can be found that reduce emissions today and create efficiencies for a future when more expensive low- and zero-carbon fuels come into the picture.

“I think that’s a win-win today, and it’s a win-win tomorrow,” he told TradeWinds.

“What we’ve done here is really trying to combine the best of sports, because we’re working with BAR Technologies, … and commercial shipping, and I think if you bring those two together, you get something that has never been done and could be a very important step in decarbonising this industry.”

How did BAR’s roots in competitive sailing translate into a new way to propel commercial ships?

Based in Portsmouth in southern England, the company emerged in 2016 out of the Ben Aislie Racing, the British team that entered the America’s Cup after its namesake served as tactician for the winning Oracle Team USA.

Because the sailing competition had long banned testing new designs by using models in tanks, the BAR team had developed sophisticated simulation techniques using computational fluid dynamics that it now uses for its designs of vessels and marine technologies.

“That’s the way we design all of our products that BAR — never tank-tested anything, never built a WindWings model before the full-size one,” said Cooper, who worked in Formula 1 motor racing before joining BAR in 2021.

“And people think we’re mad when I explain that we actually never built any model.”

But a kamsarmax bulker with its 80,000 tonnes of cargo, not to mention all the steel it’s made of, is nothing like a sleek America’s Cup yacht, so the result of applying BAR’s technique to shipping is a very different wing.

Cooper said the WindWings design is focused entirely on thrust, not overcoming hydrodynamic drag, resulting in the sails’ crescent shape.

Each wing is made up of three vertical elements separated by small gaps, features that also add to thrust.

Cooper said that each wing will save 1.5 tonnes of fuel on a large vessel each day, which equates to about 4.65 tonnes of CO2. Cargill and BAR estimate that if installed on a newbuilding, which allows a vessel to be purpose-built for wind, WindWings could slash emissions by 30%.

There are myriad designs in the market for wind-assisted propulsion, ranging from kites to Flettner rotors and other rigid sails, but Cooper is not shy about his confidence in WindWings.

“It might sound a little bit arrogant. Maybe I shouldn’t say this to you. We do think it will dominate the market,” he said.

“We feel confident in our positioning because we have a patent over quite an interesting part of the technology and what we believe makes the performance of the wing spectacular.”

The Pyxis Ocean is not the first Cargill-chartered vessel to try out wind propulsion, after the company tried out using a kite on a bulker more than a decade ago. But the effort failed to take off.

Dieleman said what was different then was that the company did not do its homework the way it has been doing with WindWings.

And there is more homework ahead.

The Cargill Ocean Transportation leader said the focus now is to see how the technology performs on the Pyxis Ocean, and that involves more than comparing its fuel savings compared to what the models predict.

“Also, how does this really work in practice? How does the technology work while you’re sailing? Those are some of the things that we’re going to learn and probably need to improve going forward, because we all know that your first prototype is not the end game,” he said.

“Then there’s also a big question: how is this going to work in ports? Because this is also new for ports, having ships with installations like this coming in. … And then, of course, we also trying to see what some of the reactions are of our customers.”

Dieleman expressed confidence that Cargill will get positive answers to most of these questions, though he acknowledged that it will take some time before the ship will be able to make enough calls to fully test port operations.

He highlighted the need for innovation as shipping confronts its greenhouse gas emissions, and innovation requires taking risks.

“What we liked around this specific project is … it was not incremental but actually quite revolutionary,” he said.

But Cargill is not putting all its wind propulsion eggs in one basket. It is also working with Japan’s NYK Group to install an Econowing wind sail on another kamsarmax.

“We’re not just betting on one technology. We believe in a broader wind-assisted propulsion programme, which will come in different forms and shapes,” Dieleman said.

Cargill Ocean Transportation is part of a growing list of shipowners and operators that have turned to wind assistance or wind propulsion, although their orders cover a small portion of the global shipping fleet.

Gavin Allwright, secretary general of the International Windship Association, said there are 30 large wind-assisted vessels in operations around the world, in addition to 10 cruise ships that have traditional sail riggings. There are another seven vessels that are “wind ready” and thus have the preparations in place to install the technology.

And an array of publicly announced orders mean that figure could rise quickly in the months ahead.

Wind is already a way to save fuel costs. But in recent months the European Union has finalised legislation to include shipping in its Emissions Trading System and the International Maritime Organization has adopted a net-zero target for greenhouse gas emissions by “around” the middle of the century, although the IMO still has work ahead before adopting new policy measures and revising existing ones to push shipping toward that goal.

- A kamsarmax bulk carrier chartered by Cargill and owned by Mitsubishi Corp has set sail after installation of the first WingSails, a wind propulsion technology developed by UK-based BAR Technologies.

- BAR Technologies estimates that each wing will save 1.5 tonnes of fuel on a large vessel each day, which equates to about 4.65 tonnes of CO2. Applied to a newbuilding, WindWings are predicted to slash emissions by 30%.

- There are an estimated 28 large ships with wind-assisted propulsion on the water today and many more on order.

- CE Delft estimates that a combination of wind-assisted technology speed reductions and zero-carbon fuels could cut international shipping’s emissions by 28% to 47% by 2030.

- Cargill is considering whether to invest in retrofitting ships for wind-assisted propulsion or focusing on newbuildings. Newbuildings make better economic sense when combined with alternative fuels.

The IMO has also adopted “indicative checkpoints” calling for 20% to 30% greenhouse gas cuts across the global shipping fleet in 2030 and 70% to 80% in 2040.

Experts believe wind can play a significant role in reaching those goals.

Allwright said that, for example, if all newbuildings were required to have wind assistance technology, it would reduce global shipping emissions by 20% by 2030.

Research consultancy CE Delft estimated in a recent report that a combination of wind-assisted technology, 20% to 30% speed reductions, and 5% to 10% zero-carbon fuels could cut international shipping’s emissions by 28% to 47% by 2030, when compared to 2008 emissions.

Under the EU’s upcoming emissions trading rules, the technology will also make a difference, as the cost of carbon credits adds to fuel expenses, improving the return on investment (ROI) for wind propulsion.

“Wind propulsion is the only propulsion system that has an ROI because … all the fuels will be more expensive,” he said, referring to the high cost of green fuels. “So it pays for itself.”

For technologies like WindWings that are being trialled, their impact will truly be felt when they can be scaled into widespread use.

BAR’s Cooper is bullish, estimating that within two and a half years, 50% of large bulker and tanker newbuildings will be ordered with wind propulsion.

“I think it is going to be that big, that quick,” he said.

Berge Bulk is gearing up to trial the sails on a large bulker (in addition to investing in BAR), and Cooper said the technology can be applied to smaller bulker carriers, even those with cranes. Tankers are even easier, and Cooper said there are interesting discussions underway with other shipping sectors like cruise.

Cargill has been weighing whether, after seeing positive results from WindWings, it should turn its focus to more retrofits or to newbuildings.

A year ago, he told TradeWinds that the company could retrofit five to 10 vessels but that newbuildings would eventually be a “game changer” because ships could be purpose-built for the technology.

Fast forward to the middle of 2023, and the advance toward zero-carbon fuels is happening faster than he expected.

“So now the question is, should we be going straight into newbuild programmes, where you have duel fuel and your paybacks are looking a lot better and actually the savings that you’re making look a lot better?” he said.

While there are reasons to retrofit existing vessels, but the economics of future fuels make a better case for investing in wind-assisted propulsion.

“If you burning a fuel that potentially is three or four times more expensive, then it’s not that difficult to do the calculation and say then that is probably the better investment,” Dieleman said.

But Dieleman said wind does not get shipping all the way to zero emissions, and it may not be the right option for 100% of the fleet.

Though wind is often described as a free fuel, the technology to harness it costs money. That investment pays off best on trades with a lot of sailing, less port time and, of course, a lot of wind. That may require changing the way wind-propelled ships are operated, the executive said.

“You might want to have a route where you will deviate a bit to get you more wind,” Dieleman said, before a final sporting comparison.

“And that’s what you see in America’s Cups. People are trying to go the route where they catch the wind, and all of a sudden, from being fifth place, they end up first.”

Read more

- Green Seas: Climate change threatens more woes ahead for gummed-up Panama Canal

- Why EU shipping emissions are unlikely to return to pre-pandemic levels

- Volatility makes for cheap entry point in European carbon market

- Capital’s ‘green revolution’, car carrier blaze rages and Xi’s disappointing growth

- ‘The cover’s off’: CargoMetrics to step up the pace of maritime data product rollouts